The Myth of Return

I was born in 1963 in a Rajshahi hospital where there had been a malaria outbreak which killed the other babies in the maternity ward. I was the lucky one.

Soon after this picture was taken, aged eight months, I boarded a plane with my Mum, Brother and Sister to London to join Dad who had won a scholarship to do a PhD in philosophy at University College London. We were classic examples of “the myth of return” – Mum had been Principal of Dhaka Women’s College and Dad was an associate professor at Dhaka University. The plan was that after about three years the PhD would have been completed and we’d all go back.

Mum had “the trunk” which most migrant settlers will know about, regularly putting things into it to take back home.

But the PhD took longer than expected, then turned into a post-doctoral programme and by the time Dad was done with UCL, we were growing up as Londoners. The three of us did well at school – especially my Brother and Sister, being Head Boy and Head Girl. I developed an early interest in becoming the Prime Minister, and took to emulating Harold Wilson, who always had a pipe in his mouth.

My first leadership role was to be head of the Balham and Tooting cub scouts, and created my first media appearance at the age of 11, centred around a performance we had staged as, would you imagine, a Black and White Minstrel show for a local old peoples’ home. That’s me in the centre, with the big hair.

I knew nothing of Bangladesh, except what I picked up from conversations between my Parents. A phrase I heard a lot was “first class first”, and one day I asked what it meant. It seemed that in Khulna, where both my Parents were from, there was just one scholarship per year for the entire region to go study at Dhaka University, and in order to qualify you had to have the highest first in the then equivalent of A levels. Both my Parents got it, met at university and married at university.

I’ve often wondered what if they hadn’t got the scholarship, what if they had been ill on the day of the exam, if there was someone better than them. We would have still been there. As I grew older, I wondered what happen to the others who applied and didn’t get the scholarship. That’s why, ever since my 20’s, Mum always got us all to pay for kids from Khulna to go through university.

Dad started to spend part of the year back in Dhaka, part in London writing books and looking after us, as by now Mum had become the first non-Christian Head of a Church of England school.

I’ve only ever been to Bangladesh twice. The first time was when I was 13. On my first day, Dad took me at the crack of dawn for an hour-long rickshaw ride around Dhaka, and I watched all these industrious people already working hard on the roads, in the markets and shops. This was around the time the US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had called Bangladesh a “basket case” and I had imagined Bangladesh must have been poor because the people were lazy. That rickshaw ride knocked that out of me.

My Brother had been five and my Sister seven when we came to London, so remembered our relatives and for the first time, I was able to put faces to the names I had been hearing all those years. I’m the one with the brown shoulder pads.

I was brought up only speaking English and with most relatives that was fine. With others, it meant improvising with facial expressions and gesticulation which every found hilarious, but somehow it worked.

My next visit was another 10 years later, and by this time I was a full-on foodie. One day I cooked a biryani for about 15 of us on an open flame on the beach in Cox’s Bazaar, pretending I was Keith Floyd. Another day we were treated to a boat launch trip to the Sundarbans, where we came across some local fishermen who had just caught some massive prawns. We bought them off them and cooked them on the boat. I remember that was a Christmas Day, and suddenly none of us were missing turkey!

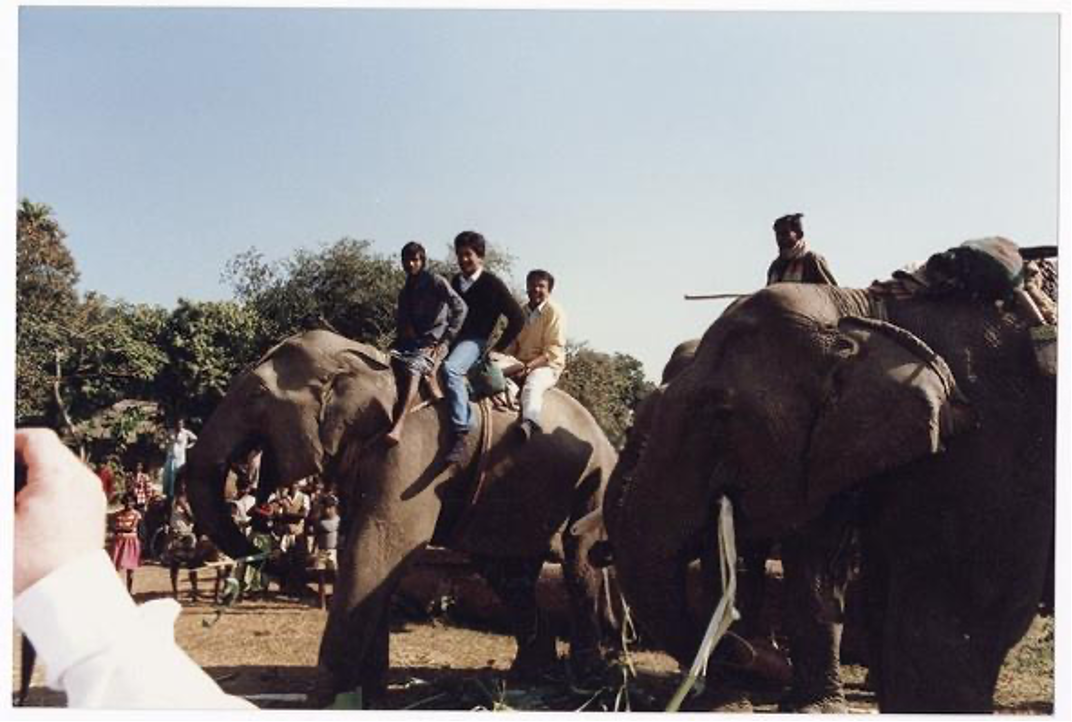

In Sylhet we stayed on a tea garden and were given an elephant ride followed by the chance to cast a net into a huge pond, and taking some of the fish we caught, slapped them straight onto a barbecue.

Back in Dhaka, a family friend took us on a boat ride for a very noble mission – to go to the old town where this old guy was famous for making one massive pot of biryani every day which was a pilgrimage many would make and boy, was it worth it!

Curiously, I never returned to my land of birth after that.

The closest I got was in 1994 when with Amin Ali and I staged the London Festival of Bangladesh in Spitalfields, which The Evening Standard described as ‘Bangladesh’s equivalent of the Notting Hill Carnival’. We flew singers, actors, and even village opera singers over, who performed what’s known as Jatra. Tens of thousands of people came to celebrate a culture I previously had little clue about. Begum Zia was prime minister at the time, and she called me The Golden Boy of Bengal. All very odd.

Apart from still helping people get an education, I have inadvertently, unintentionally drifted away from any bond with Bangladesh. My Siblings keep close links but me, not so much.

That may be changing though. I’ve often lamented the fact that with so many Bangladeshi owned restaurants there’s a hardly a single one serving Bangladeshi food. I’ve got some restaurants with different themes to them coming up but I’m also plotting a very elaborate way to celebrate the food of my (by a scratch) place of birth. I don’t feel my restaurant career will be complete without me doing that.

Written by Iqbal Wahhab OBE

Self-confessed busybody Iqbal Wahhab OBE is the founder of London restaurants The Cinnamon Club and Roast, and is the former High Sheriff of Greater London. He also works on a number of initiatives that are intended to empower British Bangladeshis to successfully raise the conditions in which many live and help build greater aspirations and ambitions for them.